In February 2017, I wrote a post on my blog about Major Douglas Dewe, a Medical Doctor serving with the British Indian Army based in Singapore during the battle. I fell into the story by chance rather than by design. I was browsing old Hong Kong newspapers when I came across an article in the Hong Kong Daily Press dated 19 August 1941 concerning the divorce of Major Dewe from his wife Rona. They had married in 1934 following the death of Major Dew's first wife.

Major Dew's marriage to Rona broke down in 1938 at about which time Rona had struck-up a relationship with a forty-year-old rubber planter in Malaya by the name of Oswald Cutler. In the August 1941 hearing, the court granted custody of the two children to Major Dewe presumably on account of his wife's infidelity. By August 1941, Major Dewe had become engaged to a charming divorcee by the name of Mrs Peggy Frampton.

The war started in December 1941, a few months after the court hearing. Major Dewe, his ex-wife Rona and Oswald Cutler all ended up in Japanese prison camps for the duration. Peggy Frampton was in Kuantan on the east coast of Malaya at the time of the Japanese invasion. She quickly collected Major Dewe's two sons and her daughter, Rae, and drove in a black Humber all the way to Singapore. Not long after Peggy's departure the Japanese landed at or around Kuantan. As Peggy Frampton drove south, the road bridges were being demolished behind her. She reached Singapore with the three children and got out on one of the last evacuation ships leaving Singapore. Peggy took the children to India where she resided during the war. Her fiancé, Douglas Dewe, survived the prison camps in Singapore and Burma. On release he found Peggy had re-married in India. Perhaps she had assumed that he had died during the battle or during the subsequent incarceration.

While updating the article on Major Dewe, I discovered a little bit more about his erstwhile fiancé, Peggy Frampton. Her husband, from whom she had divorced was Commander Pendarvis Lister Frampton. I found an old newspaper article reporting their wedding in April 1935. She is referred to as Mrs Peggy Fischer (nee Jeffries) the owner of the Garter Club in Mayfair. The couple were married at Marylebone Registry Office. When WW2 commenced Commander Frampton was assigned to HMS Sultan the shore establishment in Singapore. During the Battle for Singapore Frampton served as a Staff Officer reporting to Rear Admiral Ernest Spooner, the Senior Naval Officer in Singapore and Malaya.

Rear Admiral Spooner, Commander Frampton and Air Vice Marshall Conway Pulford were ordered to leave Singapore (just before the Fall) and re-convene at Batavia in the Dutch East Indies. Frampton and the two senior officers escaped from Singapore on the Fairmile-class motor launch ML 310. They left Singapore on Friday 13 February two days before the Fall of Singapore. They never made it to Batavia. All three senior officers died a few months later on a malarial infested island off the east coast of Sumatra. This is their story, their last story and the last voyage of His Majesty's motor launch ML 310.

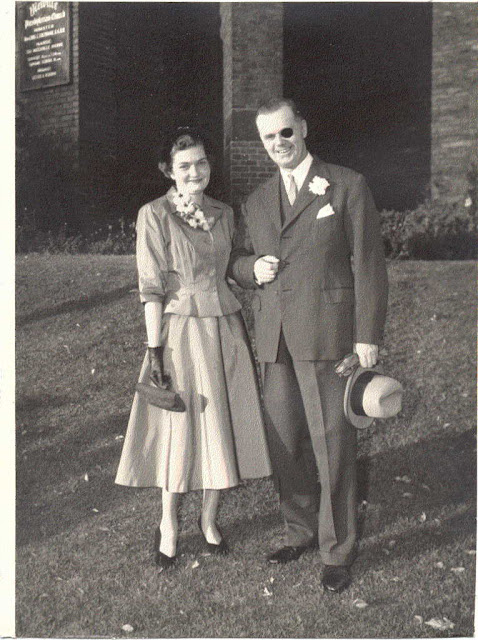

Captain P. G. Frampton & Mrs Peggy Frampton (British Newspaper archive)

Lt Richard Pool, RN, remembered waking up that Friday 13 February to the sound of the guns. The loudest being the British 15-inch and 9.2-inch coastal defence guns. The guns were designed to fire on naval targets at sea and as a result they mostly had armour-piercing shells and lacked HE and shrapnel shells more suitable for the landward firing they were by then engaged in. There had been continual air-raids and shelling. The Japanese had already landed on Singapore Island and had established a bridgehead. The Japanese had complete air dominance. The defence of Singapore had disintegrated into chaos. The evacuation of civilians and key military personnel from Singapore had been taking place in greater urgency as the Japanese advanced on the island. It resembled a mini-Dunkirk style operation with boats or every shape and size being utilised.

That afternoon Rear Admiral Spooner called a meeting in his office at Fort Canning. He told us that the decision that Singapore could not hold out had been taken and orders for all remaining Naval and Air Force personnel, as well as selected Army technicians, to leave Singapore had been given. (Lt Pool)

Lt Pool was ordered by Rear-Admiral Spooner to be ready to take him and Commander Pendarvis Frampton to Batavia in the Dutch East Indies by motor launch that night. Their party would also include Air Vice Marshal Pulford, acting as Air Officer Commanding, Far East. Spooner was married to Megan Foster a highly acclaimed soprano. She had been evacuated a few days earlier on 10 February 1942.

Rear Admiral Ernest Spooner with his wife Megan Foster

Rear Admiral Ernest Spooner with his wife Megan Foster

Lt-General Arthur Percival, General Officer Commanding British Troops in Malaya allowed Lt Ian Stonor, his ADC, to leave that same evening with Spooner and Pulford. Lt Stonor, Argyle & Sutherland Highlanders, left the Battle Box at Fort Canning with Wing-Cdr Atkins, Pulford's senior staff officer, and proceeded to the dockyard by way of Clifford Pier. They boarded the Fairmile (ML 310). Spooner, Pulford and Frampton were already aboard.

The Fairmile class motor launches were naval patrol boats armed with a 3-pdr Hotchkiss quick firing gun and deck mounted machine guns. The boats had a length of 112 ft and a displacement of 85 tons. The had twin screws and could produce a speed of 20 knots. ML 310 sailed at around 11:00 p.m.

Fairmile-class motor launch (internet)

The commander of ML 310 was Lt Jonny Bull, RNZNVR. The boat's crew consisted of eighteen men which included two officers (Lt Bull and Sub-Lt Henderson, RANVR) and Li Teng, the boat's Chinese cook also known as Charlie. In addition to the crew there were some twenty-seven military passengers making a total forty-five men aboard the ill-fated ML 310.

The twenty-seven military passengers included:

Rear-Admiral Spooner, RN

Air Vice Marshall Pulford, RAF

Commander Frampton, RN

Wing Commander Atkins, RAFVR

Lt Stonor, A&SH

Lt Pool, RN

Sgt Hornby and five Royal Marines

Two RAF other ranks.

Three Royal Engineers other ranks

Sgt Wright and four Military Police

Five RN ratings

They headed south and left Singapore in flames, ruins, disorder, and facing the bleak prospect of inevitable defeat. Shortly after leaving Singapore ML 310 developed a steering problem and later ran aground. Lt Pool, feeling responsible for Spooner and Pulford's safety, decided to go over the side in a dinghy and examine the propellors and shaft to ensure they had not been damaged in the grounding. As he came back aboard the ML his hand was badly crushed between the dinghy and the side of the launch by the strong tide.

Shortly before dawn, the tide rose sufficient for the launch to float off the reef. A few hours later they anchored close inshore at a small group of islands. The plan was to lay up during the day to avoid being spotted by Japanese warships or aircraft. They put up camouflage netting to conceal the boat. That night, 14 February they continued south and by dawn on 15 February they were approaching the Banka Straits off the coast of Sumatra. Once again they laid up during the daylight hours on 15 February. Lt Pool's injury had worsened and his whole arm was swollen. Spooner and Pulford decided to head to Muntock, a small port on Banka Island, to get medical attention for Pool's injury. Having seen few aircraft they decided that afternoon to break cover and continue in broad daylight rather than wait for nightfall.

Air Vice Marshal Pulford

While heading towards Banka Island, they were spotted by a squadron of Japanese warships including cruisers and destroyers. One of the warships opened fire and another sent off a seaplane which dropped bombs which fell astern of the launch. The launch sped towards nearby Tjebia Island with the aim of putting the island between them and the Japanese ships. The launch ran aground on a reef close inshore to the island. A Japanese destroyer was sent to intercept ML 310. They tried to re-float the vessel but to no avail. Lt John Bull, the boat's captain, Sub-Lt Henderson, the first lieutenant, Lt Pool and Wing-Cdr Atkins remained onboard, the rest of the personnel were ordered by Spooner to wade or swim ashore and conceal themselves in the jungle.

Map showing Singapore, Batavia (now Jakarta), Banka Island and Tjebia

The Japanese destroyer hove to and fired serval shots only one of which hit the launch causing minor damage. The Japanese lowered a boat with a boarding party consisting of an officer and a party of armed sailors. They came aboard the launch cuffing and hitting the four officers left onboard. The launch was already damaged but the boarding party made sure it could not be re-floated. Having finished disabling the boat, the Japanese boarding party made a semi-circle around the four captives. Their guns raised and the officer holding his sword. They were about to be shot. The officer, however, decided to spare them and allowed the four men to paddle their dinghy ashore. As they struck out towards the shore, they were expecting to be shot before they reached the beach, but the Japanese got into their own tender and returned to the destroyer.

It was a small island, about a mile long and a quarter of a mile wide with thick foliage and white sand beaches. The island was surrounded by a rocky reef. There was hill in the northern part of the island on which there was a Dutch Army radio station manned by a dozen Javanese military personnel. There was a small sparsely populated village. The few inhabitants made a living from fishing and gathering Copra. Many of the occupants had left for Banka Island. The remaining inhabitants, concerned about Japanese reprisals for harbouring British military personnel soon left the island. They took the only seaworthy fishing boats. Lt Stonor went up the hill to the radio station. The station crew had seen the launch and heard the gunfire and assumed that they were being attacked by the Japanese They had then destroyed the radio. The ML 310 passengers and crew were marooned without any form of communication.

The group decided that a party led by Lt Bull, would repair one of the fishing boats that had been left as unseaworthy, and then try and reach British forces in Batavia to alert them of the presence of the senior officers Spooner and Pulford and the rest of the group at Tjebia. The Island may have looked idyllic, like a Robinson Crusoe Island, but it was far from it. The fishermen called it 'fever island'. The island was malarial and the group of marooned servicemen were plagued by thick swarms of mosquitoes.

The air was so thick with mosquitos that we could hardly breath without getting them up our noses or into our mouths ; their vicious whine as they hovered round us was unceasing, as were their bites. Outside the hut, the chirping of millions of crickets and croaking frogs mingled with the hum of other tropical insects. (Lt Pool)

On the evening of 20 February Lt Bull, the coxswain, one RN rating, and two Javanese one of whom was the radio station commandant left in the repaired prahu for Java. Sailing and paddling at night and laying-up in the daylight they eventually reached Batavia. The naval authorities were informed and an American submarine USS S-39 was dispatched to rescue the stranded group, but although the submarine sent a party ashore they found nobody on the island. This is still a mystery, but perhaps they were on the wrong island or were not sufficiently diligent in their search.

The remaining group on the island had access to three months supply of tinned food salvaged from the wreck of ML 310. They also had access to rice that had been left behind by the villagers. There were banana, coconut and papaya trees on the island. There was water availability through wells and streams. The tinned food was rationed out. They had food but not enough of it and what they had lacked sufficient nutrients and many later developed beriberi, pellagra and other malnutrition related illnesses.

Rear Admiral Spooner was the senior officer out-ranking Air Vice Marshal Pulford. Lt Pool described Spooner as active and forceful. He had commanded HMS Repulse before being promoted to flag rank. Pulford was quiet and somewhat withdrawn. Pool described Frampton as 'a rather large, florid' man who had left the Navy and then been recalled on the outbreak of war in 1939. George Atkins was a 'quiet reflective man' who had been living in Malaya as a civilian before the war and spoke reasonable Malay. Like Frampton he had been recalled to the service. Richardson was a Warrant Officer Boatswain. Pool described him as 'old and tough'.

After Lt Bull's party had left for Batavia, the two Royal Engineer sergeants worked with Frampton to repair one of the abandoned boats. Frampton was obsessive in his determination to get off the island and sail to Batavia. After two weeks on the island, and having carried out the repairs, Frampton decided the boat was ready to be launched. They tried to launch it without sufficient rollers, but the boat fell to one side damaging and cracking the hull. It was after this setback that Frampton got ill.

Commander Frampton completely lost heart in the venture. A few days later he developed a bad chill, with violent shivering fits. With no doctor in the party, we could only suspect malaria. From this moment on, he appeared to lose all interest in the life and work on the island. (Lt Pool)

Around the end of February, there were three additions to the group. The first was Pte Docherty, Gordon Highlanders, who was found by Pool and Stonor on the west beach. He had been on another vessel that had escaped from Singapore on 13 February. The second one washed up on the same beach was a naval rating, Stoker Scammell. A few days later another survivor, Aubyn Dimmitt, an Australian civil engineer working at the naval dockyard was found on the west beach. He had been drifting in a small dinghy. All three men had been on an RAF auxiliary craft the Aquarius. The vessel had been sunk in the Banka Straits by Japanese aircraft. All three of these subsequent arrivals later died on Tjebia Island.

Commander Pendarvis Frampton died on 7 March, three weeks after landing on the island. It was later determined that he died from cerebral malaria. The absence of rescue which had been expected within a few weeks of Lt Bull's departure and the death of Frampton lowered the morale. More of the survivors got sick. There was quinine powder left on the island but some of the group were reluctant to take it because of the awful taste and the side effects like loss of hearing. Three days after Frampton's death Air Vice Marshall Pulford died. The survivors were struggling with the heat, lethargy and depression. Sub-Lt Henderson took to his bed and would not get up. He just lay there until he died. PO Keeling was on lookout duty when he developed a sore throat. His throat became so swollen that he could not swallow. He died within 24 hours. The group were suffering from a variety of illness including dysentery, malaria, beriberi and pellagra. The Javanese crew of the radio station were also effected and by this time three of their crew had died. The food stocks were running low. They estimated they had enough to last until the end of April.

Charlie, the Chinese cook, asked to go with a Javanese fishing prahu to Daboe, the principal town on Singkep Island. He claimed he had contacts there and could arrange for a fishing junk to pick up the survivors left on Tjebia. The understanding was that he would be back within a week. He reached Singkep, but did not alert anyone to their plight and he never returned. At about this time, two Royal Engineers, S/Sgt Lockett and S/Sgt Ginn left for Banka Island on a fishing prahu manned by two, apparently unsavoury-looking, Javanese. The two Royal Engineers were never seen again. It was thought they had been killed by the two Javanese boat men.

In April, Rear Admiral Spooner died. He had been a tower of strength and provided strong leadership to the marooned group. His death was sudden and unexpected. He had always appeared to be one of the fittest, but death was not discriminating. The Javanese radio station crew had suffered several deaths and the survivors had managed to get off the island probably on a Javanese prahu. Those still fit enough from the ML 310 group on Tjebia repaired another Prahu. They realised that they either got off the island or they would die on it. On 15 May, three months after they first landed on Tjebia they sailed the repaired prahu to Saya, an island between Tjebia and Singkep. The crew consisted of Atkins, Pool, Oldnall, Stonor, Johncock and Tucker. Warrant officer Richardson stayed with the sick and a few healthy men to handle the chores like the collection of water. The prahu was wrecked on the rocks of a small island near Saya. They were picked up by a fishing boat and taken to Singkep where they were held by the Javanese police and then passed to the Japanese as prisoners of war. The rest of the group on Tjebia were picked up and the group were all returned to Singapore. They arrived at Clifford Pier on 23 May 1942 and were then moved to Changi POW Camp.

Nineteen died on that forsaken fever struck island, the first of which was forty-six-year-old Pendarvis Frampton. The Commonwealth War Graves Commission cite his wife as Peggy Winifred Frampton. Perhaps she was not yet legally divorced, albeit engaged to Major Dewe. After the war the bodies of the nineteen men buried in shallow graves on Tjebia Island were exhumed and reburied at Kranji War Cemetery.

Kranji War Cemetery

Appendix 1

Fates

19 died on Tjebia Island including the three survivors from the RAF Auxiliary vessel Aqarius

1 died in Singapore

3 sailed to Batavia and survived

2 sailed to Banka Island and were missing presumed killed

1 deserted

22 of the original 45 on ML 310 were incarcerated at Changi in early June 1942

===

48 Total (excluding Dutch Army radio station crew).

===

Appendix 2

Execution of a Spy

Captain Patrick Stanley Heenan, 16th Punjab Regt, was convicted of treason after being caught spying for the Japanese during the Malayan campaign in December 1941 and January 1942. Peter Elphick and Michael Smith in their book Odd Man Out (1988) postulate that he was shot by Corps of Military Police (CMP) guards on 13 February 1942 - two days before the Fall of Singapore. This may have been ordered by Rear Admiral Spooner or by Air Vice Marshal Pulford. It is possible, that the detachment led by a sergeant (Sgt Reg Wright) consisting of four other Military Police were given the task of shooting the alleged traitor. This was done by the harbour-side with his body allowed to drop into the water. Spooner and or Pulford may have then ordered the CMP detachment to join the evacuation in ML 310.

Appendix 3

The Admiral's Wife

Rear Admiral Ernest John Spooner (22/8/1887 - 15/4/1942) married Megan Foster (1898 -1987) in 1926. She was a well-known soprano. She accompanied her husband on his last posting to Singapore as Read Admiral Malaya. HMS Scout had departed Hong Kong on 8 December 1941 with HMS Thanet. Scout was alongside the dock at Keppel Dockyard on 9 February when the First Lieutenant, Christopher Briggs, observed a car pulling up alongside the ship. It was carrying Mrs Megan Foster Spooner. Lt Briggs recalled that she was accompanied by the Admiral's steward and the Admiral's coxswain. The admirals wine cellar was brought aboard as a gift for the wardroom. 'We put Mrs Spooner in Lambton's cabin [Captain's cabin]. He had his sea cabin under the bridge. We set off as soon as it was dark, our orders were to proceed to Tanjock Prior, the port of Batavia. .... As soon as we had anchored, a boat arrived to collect Mrs Spooner and the staff. She was taken straight over to a ship, the SS City of Bedford which was sailing for Australia'. (Source: Farewell Hong Kong (1941) (2001) Christopher Briggs.

Appendix 4

Crew and passengers of ML 310 ( Source: Lt Stonor & Lt Pool)

Officers

R/Adml Ernest John Spooner, RN - Died (Rear-Admiral Malaya)

AVM Conway Pulford, RAF - Died (Air Officer Commanding)

Cdr Pendarvis Frampton, RN - Died

W/Cdr George Atkins, RAF - Survived

Lt Richard Pool, RN - Survived.

Lt Herbert Bull, RN - RNZNVR - Sailed for Batavia (CO of ML 310)

Lt Ian Stonor, A&SH - Survived (ADC to Lt-Gen Percival)

Sub-Lt Malcolm Henderson, RANVR - Died (First Lt on ML 310)

WO Boatswain Richardson, RN - Survivor. (Commissioned WO)

Other Ranks

PO Charles Fairbanks, RN - Survived (ex HMS Prince of Wales)

PO Ralph Keeling, RN - Died. (Ex HMS Repulse)

L/S Andrew Brough, RN - Sailed to Batavia with Lt Bull (ML 310 crew)

A/B Leonard Hill, RNZNVR - Sailed to Batavia with Lt Bull (ML 310 crew)

A/B Bert Gibson, RN - Died

A/B Jack Haywood, RNZNVR - Died (ML 310 crew)

A/B Robert Flower, RN - Died. (ML 310 crew)

A/B James Russell, RN - Died (ML 310 crew)

A/B Herb Oldnall, RNZNVR Survived

AB Ronald Johnson, RN - Survived (ML 310 crew)

AB Alfred Robinson RN - Died (ML 310 crew)

Sto Arthur Bale, RNZNVR - Died (Rear-Admiral's driver)

StoPO Edwin Towsend, RN - Died (ML310 crew)

Sto John Little, RN - Died

Sto Edward Tucker, RN - Survived (ML 310 crew)

Sto William Paddon (ML 310 crew)

PO MMecc H S Johncock, RN - Survived (Senior Rate on ML 310)

OrdTel Hector Smethwick, RN -Survived

OrdTel Alan Tweesdale, RN - Survived (ML310 crew)

Sgt Edward Hornby, RM - Died

Cpl Samuel Sully, RM - Died

Pte James Robinson, RM - Survived

Pte James Robinson, RM - Survived

Pte Charles Davy, RM - Survived

Pte James Sneddon, RM - survived

S/Sgt James Ginn, RE - Sailed to Batavia with Javanese (Missing)

S/Sgt John Luckett, RE - Sailed to Batavia with Javanese (Missing)

S/Sgt Richard Davies, RE - Died

Sgt Reg Wright, CMP - Survived

Cpl Stan Shieff, CMP - survived

Cpl Henry Shrimpton, CMP - Died in Singapore two days after return.

Cpl Reg Stride CMP - Survived

Cpl Jack Turner, CMP - Survived

AC Arthur Bettany, RAF - Survived

AC Norman Smith, RAF - Survived

Cook Li Ting - Deserted (Referred to as Charlie) (ML 310 )

Joined group on Tjebia Island

Pte James Doherty, Gordon Highlanders

Sto Leonard Scammell, RN

Aubyn Dimmitt Civilian civil engineer working at naval dockyard

Archive sources:

Report by Wing Cdr George Atkins, RAFVR (UKNA WO 344/362/2)

Report by Lt Ian Stoner, A&SH (UKNA)

Book sources:

Course for Disaster Richard Pool

Singapore's Dunkirk Geoffrey Brooke

Internet Sources:

Muntokpeacemuseum.org

Gallery

Lt-General Arthur Percival